| |

· www.tappi.org

· www.tappi.org

· Subscribe

to Ahead of the Curve

· Newsletters

· Ahead

of the Curve archived issues

· Contact

the Editor

|

|

|

|

Hand Papermaking as Art Therapy & Social Activism

While the idea of making paper by hand is not a new one, using papermaking as a form of art therapy and social engagement is. For Peace Paper Project, it started with a personal journey that today touches the lives of people around the world.

Peace Paper Project is an international organization of hand papermakers, art therapists, social advocates, and fine artists. Since its inception in 2011, Peace Paper Project has helped launch more than forty studios around the world—in Australia, Iran, India, Turkey, Ukraine, Germany, United Kingdom, and throughout the United States.

Serving Communities

Each Peace Paper Project studio uses traditional hand papermaking as a form of art therapy and social activism by addressing specific issues unique to their communities. The project has worked with more than 30,000 survivors of war and terrorism, human trafficking, cancer survivors, incarcerated youth, immigrants, and survivors of domestic violence.

One reoccurring program in the UK brings together ex-combatants from the IRA, English Army, and civilians caught in the crossfire during the "Troubles" (the Northern Ireland conflict). In the slums of Mumbai, Peace Paper Project has helped outfit a papermaking operation that employs women to make paper soap wrappings. Most recently, Peace Paper Project established a studio in Hamburg, Germany, where it conducts workshops with refugees from the Middle East—individuals pulp the clothing they wore as they fled their home country and transform it into sheets of beautiful handmade paper that are in turn used to tell the story of their journey.

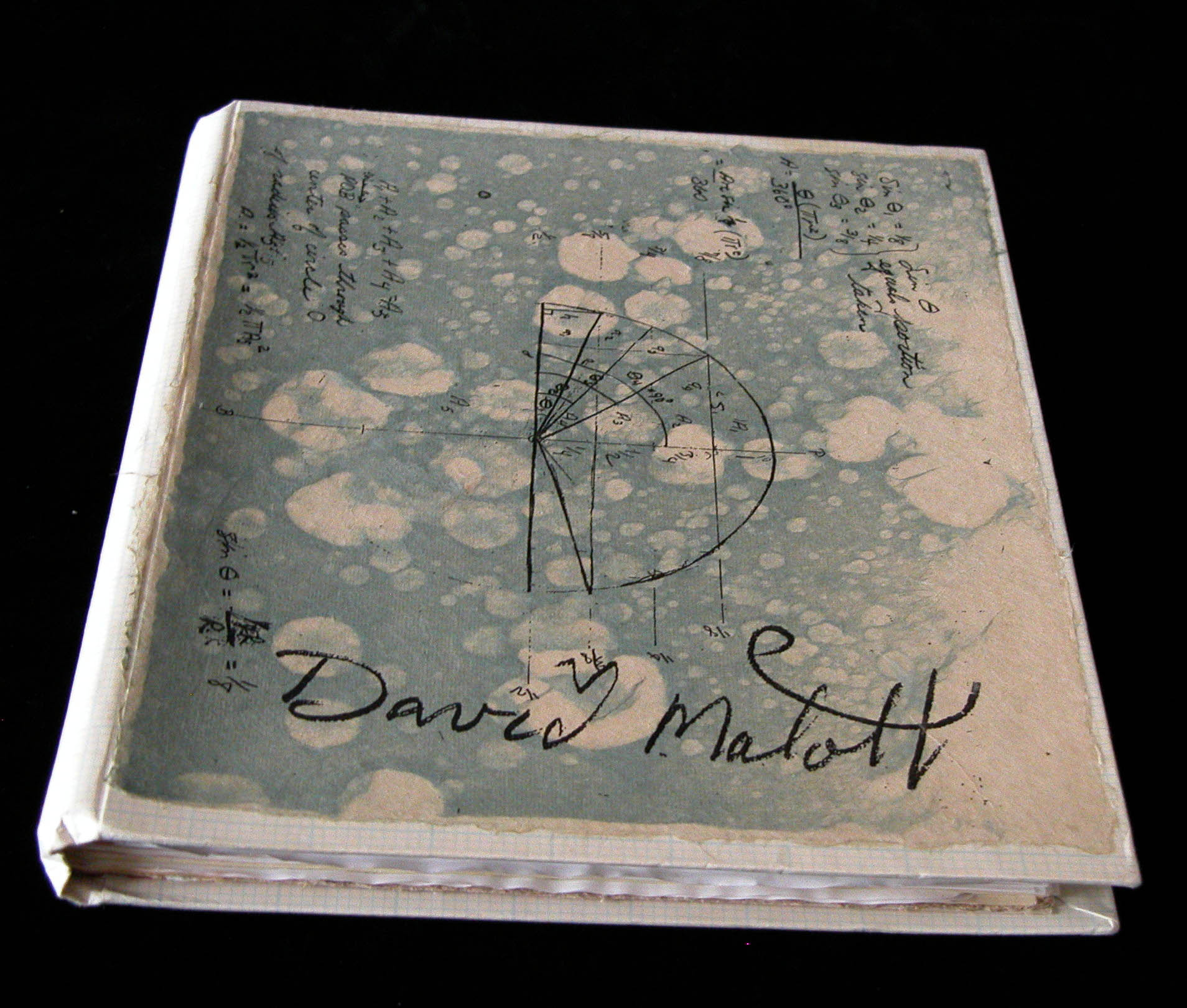

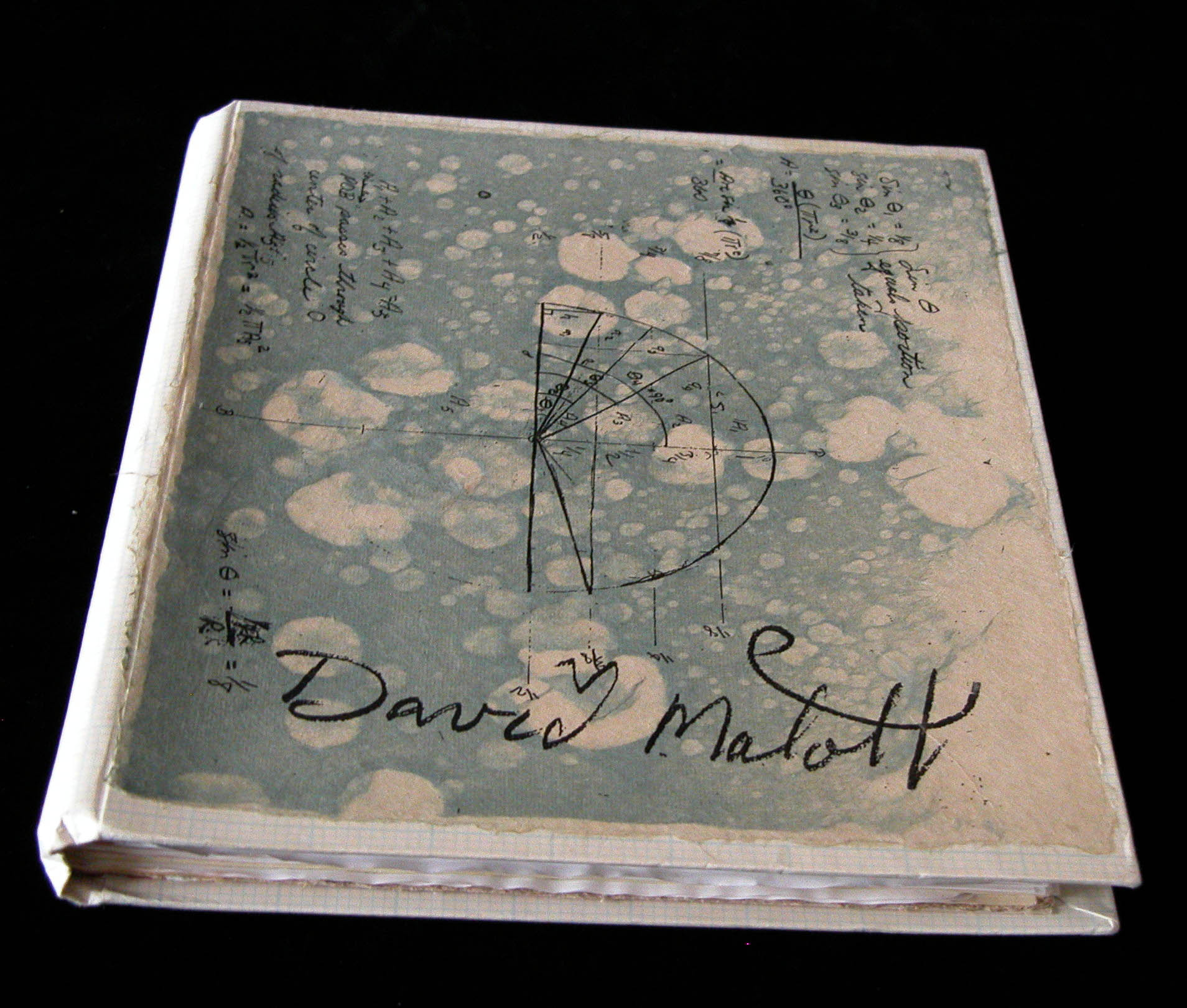

The book Matott made to honor his father, which inspired the project.

Peace Paper Project founder Drew Matott was first introduced to papermaking through his undergraduate studies at Buffalo State College, where he was required to take a class in papermaking. At first he was not on board with the idea. "As a 20-year-old printing student, I was much more interested in wearing clothes that were too small for me and trying to be cool…. But after I learned that I could make paper out of my clothes, I ran home and grabbed all my old shirts and started to cut, pulp, and make paper from them," says Matott. He brought the material into the etching, letterpress, screen printing, and lithography studios, where he began to layer prints on top of the paper.

One Family's Story

Matott's "Aha!" moment, which would become the genesis of the Peace Paper Project, came when he was home on break during that first semester. "I was going through a box of my father's things. He'd been an architect, poet, and activist, but he was killed in a car accident when I was five years old," he relates. Going through the cardboard box of the father's writings, drawings, photographs, and blueprints was the family's way to commune with their father, Matott says. On this day, at the bottom of the box Matott found a torn pair of paint-encrusted blue jeans and a few other items of clothing. As soon as his fingers touched the fabric, he thought, "What would it be like to transform this into paper?"

At first, Matott's mother hesitated when he shared his idea. She finally invited her son to make paper from the items to print some of the father's poems and photographs—"Make a set for everyone in the family," she said. Cutting and preparing the clothes for pulping became a family project, as the Matotts gathered around the dining room table and shared stories.

The young artist took the material back to the studio in Buffalo and ground it into pulp, made paper, created reproductions of the contents of the box and bound an edition of 13 books. When the semester ended, he brought the books home and traveled around delivering them to his family.

Reflecting on this journey, Matott says, "For me, the most significant encounter was when I shared the book with my uncle who was closest to my father in age. They grew up playing football, ice hockey, and fishing together. They were very close, but during the Vietnam War, my uncle felt it was his duty to protect America from the growing threat of Communism, so he enlisted in the military; my father felt it was his duty to stand for democracy by refusing the draft and protesting the Vietnam war. Ever since, the two had a strained relationship.

"I was unaware of this until I met with my uncle and handed him the copy of my father's book. My uncle is a very tough man—but when he opened the book and saw the photo of my father, he quickly closed the book and sat down, his hand resting over the book's cover… the tears just started to run down his face. Eventually he began sharing childhood stories, and told me how much he regretted not making amends with his brother."

The experience compelled Matott to dedicate his life to using papermaking as a vehicle for personal and community transformation. "At the core of the workshops, I create a space where individuals are able to create uniquely personal works; I seek to share in the powerful processes that I experienced by creating my father's book and to help activate individuals' voices."

Peace Paper Project brings hand papermaking to communities around the world.

Service to Veterans

At many US locations, Peace Paper Project is committed to providing veterans with a process that connects them with their resources, with each other, and with the communities they have served. The Veteran Paper Workshop gives veterans a platform to share their stories. Since 2011, VPW has operated internationally in universities, foundations, hospitals, art centers, shelters, and community centers to deliver a creative skill-set with the potential for enriching veterans' experiences of living their lives outside of the military.

Participants are invited to reconstitute their military uniforms into paper. Like the material itself, this process means something unique to each participant. Often, unserviceable uniforms are donated for this use to veteran centers, where they're sorted by branch before pulping. Peace Paper Project's mission is to expose care providers to hand papermaking processes, so they may incorporate these techniques into their creative arts and healing practices with veterans.

"The sight and sound of the hollander beater pulping uniforms can draw a crowd, and we use this process to connect student veterans with their advocates and peers on campuses as a way of building a support network and educating student veterans about their resources," says Matott.

"The process of making paper is a direct manifestation of resilience, as it requires breaking something down in order to create something new, useful, and beautiful," Matott concludes. "Through direct collaboration with art therapists, Peace Paper Project brings papermaking to healing populations."

Visit www.peacepaperproject.org to learn more.

For a modest investment of $174, receive more than US$ 1000 in benefits in return.

Visit www.tappi.org/join for more details. |

|