|

||||||||

| November 9, 2016 | ||||||||

| Field Report - 1 Mile Rule |  |

|||||||

|

· Subscribe to Ahead of the Curve · Newsletters · Ahead of the Curve archived issues · Contact the Editor

|

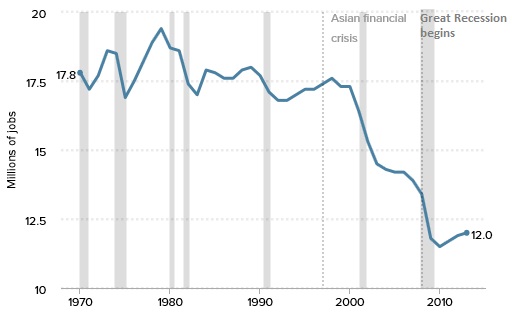

Invention, innovation and US jobs Ben Thorp, Harry Seamans, and Masood Akhtar According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) there were 17,619,000 Americans employed in the manufacturing section in January 1998; by January 2010, this figure had declined to 11,462,000 or a loss of 6,157,000 factory jobs in 12 years (Hemphill et al. 2015). This does not count the number of “consequential” jobs that were also lost. This loss of manufacturing jobs has reached the point of creating national concern. There is a need for socio-economic actions to efficiently maintain and create jobs. These days we often hear the comment “Innovation is the key to creating more jobs”. We agree, but changes must be made to make it more effective in our more global US society. Similar situations are being faced by many developed nations, but our research focuses on the US. Restoring manufacturing jobs will be difficult because the manufacturing industry is trying to use research and innovation to overcome national policy that has put the US in an unbalanced position in the world. Our analysis required extensive investigation of the real role of manufacturing jobs in an economy, and of the complex and ever-changing trade policies that are thousands of pages long and periodically amended. We have written a full-length article set to appear in the March/April issue of Paper 360°, and have prepared this preview exclusively for Ahead of the Curve readers. Today we live in a more global, less national society where more companies are international, and if a company is not yet international it will likely compete with those who are. U.S. policies established over the last several decades have helped force the international production of goods we buy. The policies favor low cost products—which is fine and good when the trade playing field is level—but due to an unlevel playing field, this has led to the loss of US manufacturing jobs. This favor toward low cost has weakened the normal result of innovation on creating jobs. Citizens ask, “What happened to the good manufacturing jobs and the communities they once supported?” One answer given frequently and far too casually is that America is the country of great innovation, and we will invent things that will create new and even better jobs. The fallacy of that notion creates a tremendous challenge. To illustrate this point, let’s examine the impact of recent invention and innovation in just one area. Look on or near your desk and you will likely see a TV, laptop, a modem, a printer, a cellphone, an iPad, and a few other electronic tools. Now let’s think about their origin. Each one was invented in the US by US companies with US citizens dominating their Boards of Directors. Now look at the labels on all of these high-tech tools at your desk: they are all made overseas. Go to other rooms and your garage, and you’re likely to find a similar situation. So perhaps we should examine what has really happened, but more importantly, what is likely to happen, and even more importantly, what we can do differently. To understand the issue, it is necessary to introduce and focus on the “jobs multiplier”: the number of jobs created by one manufacturing job. The workers employed in manufacturing need raw materials, trucks to ship finished goods, schools, dry goods stores, food stores, restaurants, hospitals, doctors, nurses, recreational facilities, local water and power plants and many other things you can name. Those jobs are called consequential jobs because without the jobs in manufacturing, fewer of the consequential jobs would exist. This concept is widely recognized, but there are wide ranges reported for multiplying factors—from 1.58 by the National Association of Manufacturers, to 16 in a case cited by Nosbasch and Bernaden (Jasinowski 2013.) There have been individual studies that have shown specific industries like coal mining have a multiplier of 4.0 (Cetnarski 2011). What is needed is a definitive study by the type of manufacturing to enable accurate estimating. For instance, it is clear that the manufacturing of goods has a higher multiplier than mining and that mining has a higher multiplier than service jobs. Manufacturing goods requires raw materials arriving at one dock and a higher-value finished product going out on another dock, which requires an infrastructure of utilities. Mining has outgoing bulk transportation, but the raw materials already exist and the utility infrastructure is small by comparison. Service jobs like teaching, nursing, doctoring, store keeping, etc. are vital and necessary, but there are no loading docks, shipping docks, and dedicated utility infrastructure. The drivers and trucks of incoming raw materials, producers of high value goods, and outgoing finished goods are missing. So service jobs have a low multiplier (many sources cite this multiplier to be less than 1.) With even this layman’s definition of multipliers, you can see how a move from a “manufacturing society” to a “service society” will result in the loss of huge numbers of jobs (Hilsenrath et al. 2016.) Any society has a limit to how many manufacturing jobs can be lost before that society’s well-being is significantly impacted, and the public is just waking up to what is really happening to the U.S. job market. In the full article to be published in the March/April issue of Paper 360°, the authors will examine what has happened; more importantly, what is likely to happen; and most importantly, what we can do differently. References:

For a modest investment of $174, receive more than US$ 1000 in benefits in return. |

|||||||

|

||||||||